In this latest blog on our January climate theme of health, we explore the links between climate, air quality and our health. This blog has been written by Met Office scientists Steven Turnock, Fiona O’Connor, Paul Agnew and Matthew Hort.

A complicated, interconnected picture

Poor air quality is one of the leading environmental risk factors to human health, with an estimated 4 million annual premature mortalities worldwide and approximately 30,000 annual premature mortalities in the UK attributed to long-term exposure to outdoor air pollutants. Elevated concentrations of certain pollutants can also lead to other environmental impacts, including poor visibility, reduced crop yields and damage to buildings and vegetation. Poor air quality episodes can cover geographic areas from a single city to larger regions, and normally last from days to weeks.

Certain air pollutants (such as ozone (O3) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5)) are also ‘radiatively active’, which means they can influence the climate by providing additional warming or cooling. These pollutants are identified as short-lived climate forcers (SLCFs) because they reside in the atmosphere for a short period of time (less than 1 year), meaning their impact on climate is also shorter (within 2 decades) than long-lived greenhouse gases such as carbon-dioxide (CO2).

Climate change can also influence the concentrations of air pollutants, with warmer temperatures projected to have detrimental impacts on surface air quality across several regions (e.g., South Asia) in the future. It is also expected to increase the frequency of hot and cold weather events, which may also adversely impact our health. As shown in the graphic below, this leads to a complicated, interconnected picture between health, air quality and climate, where future changes to one can strongly impact the other.

What we are doing to better understand the interactions

Within the Met Office, we undertake research on air quality, both at local scales over days to weeks, and at the global scale for periods of decades up to 100 years into the future.

Scientists in the Met Office Hadley Centre have been working on numerous collaborative initiatives, including the Climate Science for Service Partnership China (CSSP China) project (supported by the UK Government’s Newton Fund), to better understand how climate and air quality interact. A large part of this work contributes to the World Climate Research Programme’s 6th phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), which seeks to provide a better understanding of the past, present and future climate.

Our scientists have been analysing what the different future climate and air pollutant pathways mean for SLCFs and their impact on both climate and air quality. Our research shows that significant reductions in all air pollutants are beneficial to climate, air quality and human health, whereas there are some negative impacts on air quality and health across regions such as Africa if there are not future reductions in air pollutants. Therefore, it is important to consider the impact on air quality and health from future changes in these SLCFs.

Methane is another important SLCF. It is the second most important greenhouse gas after carbon-dioxide, albeit shorter lived in the atmosphere, and it contributes to poor air quality globally by forming ozone in the lower atmosphere. Efforts to control atmospheric methane may help to reduce the near-term future rate of warming, along with substantial reductions in surface ozone – providing clear climate and air quality benefits.

A pledge agreed at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change conference (COP26) to reduce global methane emissions from human activity by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030, has the potential to deliver benefits to climate, air quality and human health. Analysis from the United Nations Environment Programme’s Global Methane Assessment suggests that the 30% emissions’ reductions could result in 0.3°C of avoided warming over the next two decades.

Corresponding decreases in surface ozone could reduce premature deaths from poor air quality by over a quarter of a million and prevent more than half a million visits to accident and emergency departments from asthma globally every year. Using new methane modelling capability, the Met Office is working with partners in the UK academic community to quantify these outcomes. We will also assess how changes in emissions other than methane may affect the climate, air quality and health impacts.

Our local air quality forecasts

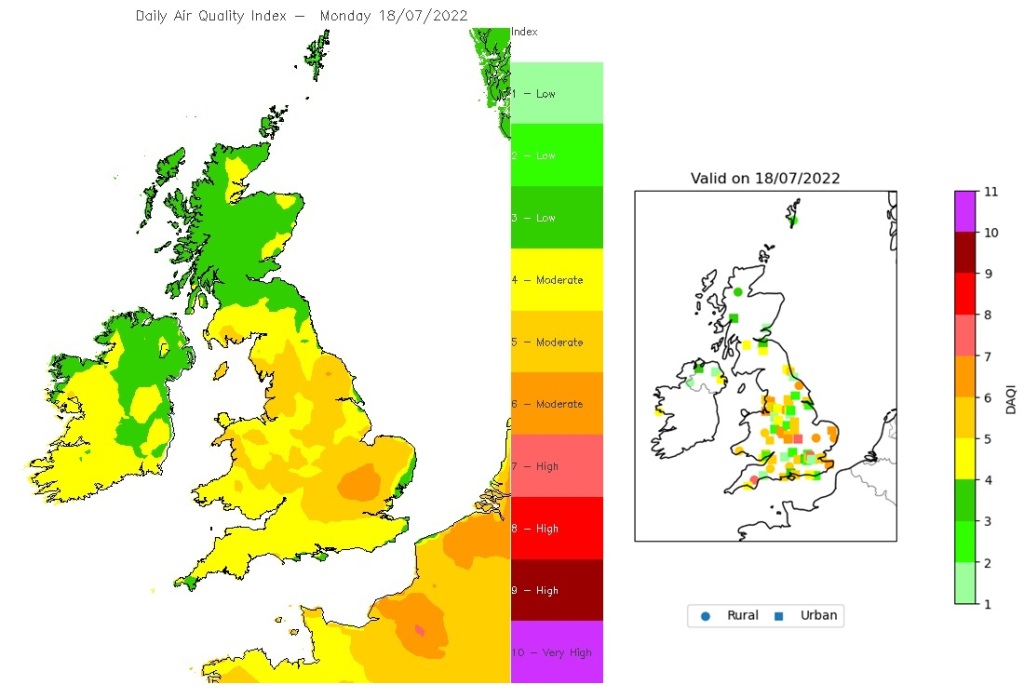

The Met Office produces a 5-day forecast of the Daily Air Quality Index (DAQI) for the UK. The DAQI is a representation of pollutant concentrations time-averaged throughout the day and gives an indication of overall air quality. The forecast is provided to Defra, as the government department responsible for air quality in the UK, for display on their website, and the data is also used in the Met Office weather app. The air quality forecast is made by combining a computer model for atmospheric chemistry and aerosols with recent observations from the Automatic Urban and Rural Network (AURN) of air pollution monitors. The observations are also used to check the accuracy of the forecast, as illustrated below.

Improving the understanding of air quality and health

The Met Office is involved in several research and development projects to improve our air quality forecast, and to further understand the links between air quality and human health. A core activity is the development of a new modelling framework which will permit an improved forecast resolution.

Another research topic, funded by the Clean Air Programme and delivered by the Met Office, concerns the production of a UK air quality ‘re-analysis’. This will use past observations and a modern computer model to provide estimates of hourly pollutant concentrations from 2003 to the present day for the whole of the UK. When compared alongside health records of the UK population, this new dataset has the potential to provide insight and improved understanding of the impacts of poor air quality on human health across different regions and following episodes of elevated pollution levels.

The future of air pollution and health

Poor air quality continues to be an important environmental issue, posing a considerable threat to our health both in the UK and around the world. The future direction of travel, in terms of human-induced emissions, could either worsen or improve this situation and have unintended consequences for climate. The Met Office is at the forefront of research that looks at improving our understanding of the interaction between health, air quality and climate. This will help us to make better predictions of air quality across a wide range of spatial (local to global) and temporal (days to decades) scales, enabling us to help people make better decisions to stay safe and thrive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.